People keep telling me I write traditional fantasy. They’re usually being nice when they say that, otherwise they probably would have called it derivative, so don’t get me wrong, I’m totally happy with the label. But to be honest with you, I’m not sure I know what ‘traditional fantasy’ even means. Or rather, I’m not sure what it means to them, the people using the term. Their perceptions may not be the same as mine.

That’s the thing with labels like ‘traditional’: I want to know whose traditions are being referenced. Y’know, just so we’re clear. There’s nothing worse than having a debate that isn’t actually a debate at all, because we’re talking about the same things, just using different terms to describe them.

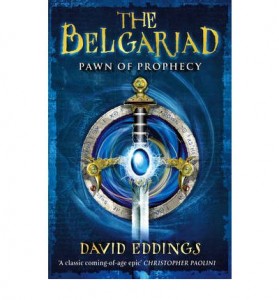

When I think of traditional fantasy, I default to the likes of David Eddings’ Pawn of Prophecy: a Chosen One raised in obscurity to keep him safe, who goes off on a quest with a motley band of adventurers (including a feisty girl that the bewildered, nice-if-a-bit-dim protagonist hates at first but will ultimately marry) leading to a glorious destiny at the end. Probably involving a throne. Black hats and white hats are readily identifiable, motives are rarely murky, and it’s a pretty good bet you know how it’s going to end.

When I think of traditional fantasy, I default to the likes of David Eddings’ Pawn of Prophecy: a Chosen One raised in obscurity to keep him safe, who goes off on a quest with a motley band of adventurers (including a feisty girl that the bewildered, nice-if-a-bit-dim protagonist hates at first but will ultimately marry) leading to a glorious destiny at the end. Probably involving a throne. Black hats and white hats are readily identifiable, motives are rarely murky, and it’s a pretty good bet you know how it’s going to end.

Another trope that I closely associate with ‘traditional’ is the protagonist being somebody’s heir, descendant or a hero reborn. Their destiny is pre-determined and thus their agency is limited because of who they are, so I would put the Shannara books in that category too (although I gather that in later volumes the story tries to get ‘bigger’ and move beyond this). I’d likely throw The Wheel of Time in there too: it certainly started out that way, before Rand got over being a whiny brat, accepted his fate and owned it.

Speaking of prophecy, characters getting pushed around by one is yet another hallmark of what I’d class as traditional. After all, prophecy is a common motif in the myths and religious traditions that fuel much of our storytelling: Ragnarök, Achilles’ heel, auguries etc. As an indiscriminate and voracious teen reader I gobbled up fantasy like that, but these days it chafes a bit. I like to see more characters figuring stuff out as they go and getting thrown off track by their mistakes, rather than just following signposts.

A more general definition of traditional fantasy encompasses those stories which draw on a particular mythic heritage, usually European, usually set in a pseudo-medieval* secondary world, with non-urbanised, non-industrial feudal societies, before the invention of firearms. In other words, a society in which the existence of magic can’t be argued away by actual science. I can see why people would apply that definition to The Wild Hunt, although personally I don’t think the shoe quite fits. It’s pinching my toes and there’s a blister on my heel.

The Empire I wrote about has a state press (at least in the capital), mass-printed books, accurate clocks, mechanised weaving, quite widespread literacy, numerous universities, and some indoor plumbing, all referenced in the text, and none of it dependent on magic, only human ingenuity. By those lights, I wouldn’t call it ‘pseudo-medieval’ at all – it’s more ‘pseudo-early modern’.**I’ve tried to portray it as a society on the verge of a technological leap: they already import fireworks, so it’s only a matter of time before someone starts looking closely at their explosive properties, and the military applications thereof.***

The Empire is also only a titular monarchy, and the Emperor does not have absolute power. He requires a consensus in his privy council, whose members are regional governors for each of the provinces in the Empire (which were once kingdoms in their own right) and if they chose to revolt, they could vote for the appointment of a new Emperor. Yes, really. No divine right of kings here.

There’s no band of plucky adventurers either. Most of the time Gair’s alone, or with one or two people, who are not constant companions but move in and out of the action as needed – and the feisty girl is an older woman who makes no secret of the way she feels.

I will cop to the wandering magus trope, however, and the fact that there is some mystery over Gair’s parentage, although I tried to poke fun at that a little:

‘You know, that has the ring of a story to it,’ Alderan said. ‘The orphaned boy with the crown-shaped birthmark that identifies him as the lost heir to the kingdom, and so forth.’

Gair shook his head. ‘No crowns. No kingdoms. Just a soldier’s brat put out to charity.’

— Songs of the Earth

The truth is exactly what Gair believes it to be: his mother couldn’t keep him and his foster family didn’t want to, so he ended up raised by the Church. But when the music stops and the story ends, he will not be the king of anything.

I used those tropes deliberately, knowing I would get flak for them, because they fitted the story I was telling. I’ll use whatever tools are available to me to build what I want. Besides, I’m nowhere near well-enough read in the genre to know the minutiae of everything that’s been done before and therefore attempt to create something entirely new; the story came first and the world evolved around it. If all this makes me a writer of traditional fantasy, then so be it.

So I circle back to the original question: what does traditional fantasy mean for you? Is it the setting, the plot, the protagonist’s origin story? Is it the archetypes the author uses, the mythos they chose to draw from? Does it even matter to you, as a reader, as long as the characters are engaging and the story’s fun?

Is a bit of tradition really a bad thing?

***

* A personal grumble of mine: I get a tad irritated when folk use the term ‘medieval’, which refers to the Middle Ages, as some kind of lazy catch-all for any pre-industrial society. The Middle Ages were on their way out by the time Gutenberg produced his folio Bible in 1455. Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and his anatomical sketches were maybe fifty years away, and both Oxford and Cambridge had colleges that were by then already almost 200 years old.

** I studied early modern history, so I drew on that in building my world. The Tudor era, the dissolution of the monasteries, the Reformation, the whole nine yards.

*** Consider the proliferation of firearms in our world, spreading westwards from China into Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries, and the evolution of personal rather than battlefield weapons. Yes, considering the timelines of other technological developments I appropriated from European history, the Empire should probably have at least prototype mortars by now, but this was one area I deliberately chose not to explore in these books. I had plenty else to deal with. Besides, the trade routes up from the lands beyond Arkadie are risky, so it’s hard to bring new ideas home. Ships are lost all the time to storms and piracy. It’s entirely possible there are cast bronze cannon already languishing at the bottom of the Inner Sea with the Empire’s equivalent of the Mary Rose.